|

What Happened to the American Economy?

October 2009

Official U.S. unemployment rate jumped to 10.2%.

search

June 1, 2009

GM

bankruptcy announced. search

April

30, 2009

Chrysler

bankruptcy announced. search

Sept.

19, 2008

Treasury announces guaranty program for money market funds. search

Sept.

18, 2008

Run on money

markets.

search

Sept.

15, 2008

Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy (case

study). search

Sept.

7, 2008

Federal takeover of

Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac, a conservatorship. search

July

17, 2007

Bear

Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Funds collapse

(House

of Cards).

search

A

Massive Economic Contraction!

Contraction in Percentage of U.S.

Civilian Population Employed

and U.S. Housing Starts

Why did this happen?

The economic contraction occurred

because of poor risk management during the liberalization of financial markets.

There were too many unwise steps

taken to reduce capital reserves for potentially high-risk loans.

Capital reserves are the money that banks and other financial

institutions must keep on hand as a cushion against losses.

| Brokerage

Firms |

Government Sponsored Enterprises

(GSE) |

Banks |

| NEW

RULES

April 28, 2004

U.S. market regulators approved new rules that would let some major Wall Street brokerages reduce the amount of money they set aside as net capital, in some cases by as much as 30 percent. In a move in line with bank regulatory changes in Europe, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission voted unanimously in an open meeting to approve two optional sets of rules. Under one of them, five big U.S. brokerages

could be designated as "consolidated supervised entities," or

CSEs.

Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns

expressed interest in CSE status. In line with new capital adequacy standards coming into force soon under Europe's Basel accords, brokerages granted CSE status would be able to use in-house, risk-measuring computer models to figure how much net capital they need to set aside. Under Basel standards, some institutions could

cut their net capital by as much as 50 percent. But the SEC's new CSE rule added a $5-billion floor to the Basel model, reducing the likely level of reductions to 20 to 30 percent.

source | search

AFTER THE FALL

September 26, 2008

Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Christopher Cox today announced a decision by the Division of Trading and Markets to end the Consolidated Supervised Entities (CSE) program, created in 2004 as a way for global investment bank conglomerates that lack a supervisor under law to voluntarily submit to regulation. Chairman Cox also described the agency's plans for enhancing SEC oversight of the broker-dealer subsidiaries of bank holding companies regulated by the Federal Reserve, based on the recent Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the SEC and the Fed.

Chairman Cox made the following statement:

The last six months have made it abundantly clear that voluntary regulation does not work. When Congress passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, it created a significant regulatory gap by failing to give to the SEC or any agency the authority to regulate large investment bank holding companies, like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Lehman Brothers, and Bear Stearns.

Because of the lack of explicit statutory authority for the Commission to require these investment bank holding companies to report their capital, maintain liquidity, or submit to leverage requirements, the Commission in 2004 created a voluntary program, the Consolidated Supervised Entities program, in an effort to fill this regulatory gap.

As I have reported to the Congress multiple times in recent months, the CSE program was fundamentally flawed from the beginning, because investment banks could opt in or out of supervision voluntarily. The fact that investment bank holding companies could withdraw from this voluntary supervision at their discretion diminished the perceived mandate of the CSE program, and weakened its effectiveness.

The Inspector General of the SEC today released a report on the CSE program's supervision of Bear Stearns, and that report validates and echoes the concerns I have expressed to Congress. The report's major findings are ultimately derivative of the lack of specific legal authority for the SEC or any other agency to act as the regulator of these large investment bank holding companies.

With each of the major investment banks that had been part of the CSE program being reconstituted within a bank holding company, they will all be subject to statutory supervision by the Federal Reserve. Under the Bank Holding Company Act, the Federal Reserve has robust statutory authority to impose and enforce supervisory requirements on those entities. Thus, there is not currently a regulatory gap in this area.

The CSE program within the Division of Trading and Markets will now be ending.

source | search

|

NEW

RULES

March 19, 2008

OFHEO, Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac today announced a major initiative to increase

liquidity in support of the U.S. mortgage market. The

initiative is expected to provide up to $200 billion of

immediate liquidity to the mortgage-backed securities

market.

OFHEO estimates that Fannie Mae’s

and Freddie Mac’s existing capabilities, combined with this

new initiative and the release of the portfolio caps announced

in February, should allow the GSEs to purchase or guarantee

about $2 trillion in mortgages this year. This capacity will

permit them to do more in the jumbo temporary conforming

market, subprime refinancing and loan modifications

areas.

To support growth and further

restore market liquidity, OFHEO announced that it would begin

to permit a significant portion of the GSEs’ 30 percent

OFHEO-directed capital surplus to be invested in mortgages and

MBS.

source

| search

AFTER THE FALL

September 7, 2008

In order to restore the

balance between safety and soundness and mission, FHFA has

placed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship. That

is a statutory process designed to stabilize a troubled

institution with the 5 objective of returning the entities to

normal business operations. FHFA will act as the conservator

to operate the Enterprises until they are stabilized.

The goal of these actions is to

help restore confidence in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, enhance

their capacity to fulfill their mission, and mitigate the

systemic risk that has contributed directly to the instability

in the current market.

source

| search

|

NEW

RULES

1980-1992

The Monetary

Control Act of 1980 (MCA) mandated universal reserve

requirements to be set by the Federal Reserve for all

depository institutions, regardless of their membership

status.

To ease the burden of reserve

requirements, the MCA initially set the basic reserve

requirement on transaction deposits at 12 percent — below

the 16.25 percent maximum that had been in effect for member

banks — and prohibited the Federal Reserve from raising this

requirement above 14 percent. It also set a 3 percent reserve

requirement on the first $25 million of deposits at each

institution — the so-called low reserve tranche — as a

special concession to smaller depositories.

In 1982, the Garn–St Germain

Act went even further by exempting from reserve requirements

altogether the first $2 million of deposits. The law mandated

annual adjustments to the cutoffs for the exemption and the

low reserve tranche based on aggregate growth in reservable

liabilities and transaction deposits respectively. To help

smooth the transition for nonmember banks and thrift

institutions, a multiyear phase-in period was put in place,

and the Federal Reserve was also prohibited from putting

reserve requirements on personal time and savings deposits,

which were particularly important sources of funds for these

institutions.

In the decade after passage of

the MCA in 1980, the Federal Reserve left reserve requirements

essentially unchanged. More recently, however, it has taken

two steps to reduce these requirements. In December 1990, the

required reserve ratio on nontransaction accounts —

nonpersonal time and savings deposits and net Eurocurrency

liabilities — was pared from 3 percent to zero, and in April

1992, the 12 percent requirement on transaction deposits was

trimmed to 10 percent.

source

| search

1994-2008

Since 1994,

depository institutions have been able to lower required

reserves without affecting customer liquidity by periodically

reclassifying balances from retail transactions deposits into

savings accounts. This practice, known as

"sweeping," has grown rapidly, and, as a result,

reserve requirements as a percentage of total liquid deposits

have fallen dramatically.

source

Since January 1994, the Federal

Reserve Board has permitted depository institutions in the

United States to implement so-called retail sweep programs.

The essence of these programs is computer software that

dynamically reclassifies customer deposits between transaction

accounts, which are subject to statutory reserve requirement

ratios as high as 10 percent, and money market deposit

accounts, which have a zero ratio. Through the use of such

software, hundreds of banks have sharply reduced the amount of

their required reserves. In some cases, this new level of

required reserves is less than the amount that the bank

requires for its ordinary, day-to-day business. In the

terminology introduced by Anderson and Rasche (1996b), such

deposit-sweeping activity has allowed these banks to become

“economically nonbound,” and has reduced to zero the

economic burden (“tax”) due to statutory reserve

requirements.

source

Bank reserves

effectively near zero for over a decade.

Required Reserves minus Vault Cash

source

During the 1990s,

Federal Reserve publications have documented the spread of

deposit-sweeping software through the U.S. banking industry.

The July 1994 Humphrey-Hawkins Act monetary-policy report

introduced deposit-sweep programs, in a single sentence. The

July 1995 report noted that approximately $12 billion of

deposits were involved in sweep activity and, as a result,

that deposits at Federal Reserve Banks had decreased by about

$1.2 billion. It also raised concern regarding an increase in

federal funds rate volatility if deposits decreased further.

The July 1996 report included a special appendix on the

operation of sweep programs. The February 1997 report noted

that the aggregate amount of deposits affected by sweep

programs had increased to approximately $116 billion, compared

to $45 billion in 1995. The July 1997 report noted the

introduction of deposit-sweep programs for household demand

deposits, and noted that some banks were increasing the size

of their clearing balance contracts when sweep programs

reduced their required reserves. Subsequent reports have

repeated these themes, along with an appeal that the Congress

allow the Federal Reserve to pay interest on reserve balances.

source

| search

AFTER THE FALL

October 6, 2008

The Federal Reserve Board

announced that it will begin to pay interest on depository

institutions' required and excess reserve balances.

The Financial Services

Regulatory Relief Act of 2006 originally authorized the

Federal Reserve to begin paying interest on balances held by

or on behalf of depository institutions beginning October 1,

2011. The recently enacted Emergency Economic Stabilization

Act of 2008 accelerated the effective date to October 1, 2008.

Employing the accelerated

authority, the Board has approved a rule to amend its

Regulation D (Reserve Requirements of Depository Institutions)

to direct the Federal Reserve Banks to pay interest on

required reserve balances (that is, balances held to satisfy

depository institutions' reserve requirements) and on excess

balances (balances held in excess of required reserve balances

and clearing balances).

The interest rate paid on

required reserve balances will be the average targeted federal

funds rate established by the Federal Open Market Committee

over each reserve maintenance period less 10 basis points.

Paying interest on required reserve balances should

essentially eliminate the opportunity cost of holding required

reserves, promoting efficiency in the banking sector.

The rate paid on excess

balances will be set initially as the lowest targeted federal

funds rate for each reserve maintenance period less 75 basis

points. Paying interest on excess balances should help to

establish a lower bound on the federal funds rate. The formula

for the interest rate on excess balances may be adjusted

subsequently in light of experience and evolving market

conditions.

source

| search

|

What was done to

address the economic contraction in 2008?

The

monetary base was increased to cover the dangerous lack of capital reserves.

The U.S. Treasury created billions of

additional dollars, and the Federal Reserve used the dollars to

purchase high-risk loans from financial institutions, and provided

overnight loans as needed, to keep the institutions solvent.

Massive Increase in the Monetary Base

since 2008

Monetary Base (dollars in circulation

and central banks' reserves) source

Federal Reserve Assets 2007-2011 source

After the collapse of

Lehman Brothers in 2008, the Federal Reserve rapidly increased the monetary base to

fund a variety of short-term programs to stabilize financial institutions by

providing them with much needed reserves. Included were programs supporting

banks, money market mutual funds, and primary dealers (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill

Lynch, etc.)

[see Chart D below]. Funds were also used to support

foreign central banks through currency swaps. In 2009, as funding

for the short-term programs was reduced, a massive transfer of

high-risk ("toxic") mortgage-backed securities to the

Federal Reserve occurred to provide banks with more excess reserves

[see Charts D & E

below].

High Excess Reserves of Depository Institutions

since 2008

Excess Reserves of Depository Institutions

source

60 Minutes Asks Why Isn't

Anybody in Jail for the Financial Crisis?

source

Why all the risky

loans?

The desire for "affordable" home

loans was a key component of the economic contraction in 2008.

High-risk

mortgage loans were pushed by a do-gooder federal government, and

accepted by many borrowers and lenders.

As long as home values continued to increase, the high risks of many mortgage loans

were

"hidden" from view. Once home prices began to fall in

2007, an economic contraction was just around the corner.

U.S. House Price

Index

House Price Index for the U. S.

source

What were borrowers and lenders

thinking?

|

Mortgage

Borrowers

|

Federal

Government

|

Mortgage

Lenders |

|

A 20% mortgage loan down

payment is "not fair".

Historically, mortgage

borrowers were required to make a 20% down payment. The lender

was protected from any potential loss in the mortgaged home

value by lending out only 80% of the selling price.

Many mortgage borrowers would

like to avoid a 20% down payment, especially if they are

first-time or low-income home buyers, and they were happy when

mortgage lending practices changed to include...

NINA loans

A type of reduced documentation mortgage program in which no

income and no assets are disclosed on the loan application,

but employment is verified.

NINJA loans

A type of loan extended to a borrower with "no income, no

job and no assets".

For comparison, risk-averse lenders would require the

borrower to verify a stable income and sufficient collateral,

but a NINJA loan process ignores such verification.

125% loans

A mortgage loan with a borrowed amount equal to 125% of the

initial property value. The borrower gets a mortgage loan with

no down payment, and with an addition loaned amount for 25% of

the value of the property being mortgaged.

|

Federal

government "stability", "assistance" and

"access" is created.

The Federal

National Mortgage Association, nicknamed Fannie Mae, and the

Federal Home Mortgage Corporation, nicknamed Freddie Mac, have

operated since 1968 as government sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

This means that, although the two companies are privately

owned and operated by shareholders, they are protected

financially by the support of the Federal Government. These

government protections include access to a line of credit

through the U.S. Treasury, exemption from state and local

income taxes and exemption from SEC oversight.

Fannie Mae was created in 1938 as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal.

Initially, Fannie Mae operated

like a national savings and loan, allowing local banks to

charge low interest rates on mortgages for the benefit of the

home buyer. This lead to the development of what is now known

as the secondary mortgage market. Within the secondary

mortgage market, companies such as Fannie Mae are able to

borrow money from foreign investors at low interest rates

because of the financial support that they receive from the

U.S. Government. It is this ability to borrow at low rates

that allows Fannie Mae to provide fixed interest rate

mortgages with low down payments to home buyers. Fannie Mae

makes a profit from the difference between the interest rates

homeowners pay and foreign lenders charge.

For the first thirty years

following its inception, Fannie Mae held a veritable monopoly

over the secondary mortgage market. In 1968, due to fiscal

pressures created by the Vietnam War, Lyndon B. Johnson

privatized Fannie Mae in order to remove it from the national

budget. At this point, Fannie Mae began operating as a GSE,

generating profits for stock holders while enjoying the

benefits of exemption from taxation and oversight as well as

implied government backing. In order to prevent any further

monopolization of the market, a second GSE known as Freddie

Mac was created in 1970. Currently, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

control about 90 percent of the nation's secondary mortgage

market.

source

FEDERAL

HOME LOAN MORTGAGE CORPORATION ACT

Approved July 24, 1970

As amended through July 21, 2010

It is the purpose

of the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation—

(1) to provide

stability in the secondary market for residential

mortgages;

(2) to respond

appropriately to the private capital market;

(3) to provide

ongoing assistance to the secondary market for residential

mortgages (including activities relating to mortgages on

housing for low- and moderate-income families involving a

reasonable economic return that may be less than the return

earned on other activities) by increasing the liquidity of

mortgage investments and improving the distribution of

investment capital available for residential mortgage

financing; and

(4) to promote

access to mortgage credit throughout the Nation (including

central cities, rural areas, and underserved areas) by

increasing the liquidity of mortgage investments and improving

the distribution of investment capital available for

residential mortgage financing.

source

"I do think I

do not want the same kind of focus on safety and soundness

that we have in OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency] and OTS [Office of Thrift Supervision]. I want to

roll the dice a little bit more in this situation towards

subsidized housing"

-- Rep. Barney Frank,

House Financial Services Committee hearing, Sept. 25, 2003

|

Mortgage Loan

Reselling Historically,

most mortgage companies and banks serviced their mortgage

loans after they originated them. Before making a loan, they

took into account a potential borrower’s financial status

and history, spending habits, and existing relationship with

the lender, if there was one. Each lender had a great

incentive to see that the mortgage was repaid in full and on

time. More recently,

it has become common for loan originators to quickly resell

their mortgage holdings to companies that specialize in

servicing mortgage loans. In some cases, a mortgage loan is

resold several times. Resold mortgages are often packaged into

mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The

practice of reselling mortgages can foster a higher level of

risk taking on the part of the lender, since the loan

originator can be less concerned with the loan repayment, as

they do not hold the loan very long. The repayment risk is

passed on to the business servicing the loan after it is

resold. Also,

about 90 percent of the mortgages written in the past few

years are backed by the federal government — mainly through

Fannie, Freddie or the Federal Housing Administration —

which implies that some loan risk can be shifted to the

government (in extreme cases). The

other 10 percent of mortgage loans are typically loans that

are too large to be covered by government programs, or loans

that the lenders decided to keep on their books for some other

reason. Such lenders include community banks and credit unions

— two types of institutions that have long embraced an

old-fashioned, common-sense approach to mortgage lending. |

Why the BIG reduction in home prices?

A price

"bubble" starts with an exuberant rise from strong demand, which is then

followed by an unplanned fall during weak demand.

For several years

after 2000 the rise in U.S. home prices outpaced the historical

norm, but in 2007 prices started to drop toward that norm.

U.S. House Price

Index

Red dashed line is estimate of

historical norm.

Why did the BIG reduction in home

prices damage the U.S. economy so much?

|

Equity Losses

|

Job Losses

|

Leveraged

Losses |

| A dramatic

fall in home equity.

Perhaps the most defining

aspect of the 2007 recession, and by many considered to be the

origin of the financial crisis, has been the decline in the

housing market.

An important consequence of the

initial increase and subsequent fall in average house prices

for households is the dramatic fall in home equity.

When home prices began to fall

in 2007, owners’ equity in household real estate began to

fall rapidly from almost $13.5 trillion in 1Q 2006 to a little

under $5.3 trillion in 1Q 2009, a decline in total home equity

of over 60%.

With the loss in home equity, a

growing proportion of homeowners in fact lost all equity in

their homes, finding the mortgage debt on their property to

exceed its current market value.

Among homeowners with

mortgages, at the end of 2009, 21% reported to be “underwater”

at the time of the survey.

source |

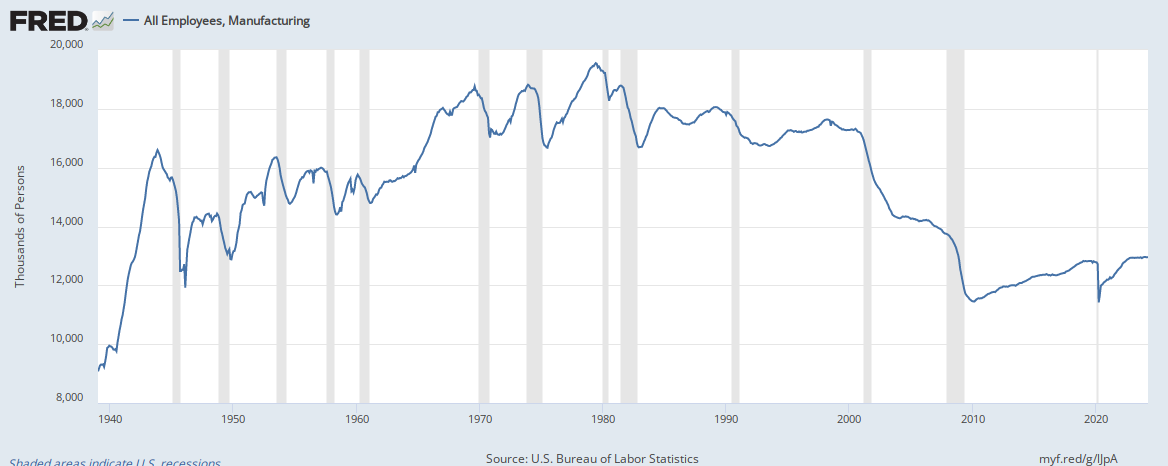

Employment in the U.S. dropped in

part due the loss of construction jobs, adding to the earlier loss

of jobs in manufacturing.

Shortly after home prices peaked in

2007, the number of new houses being built dropped dramatically.

This resulted in a massive loss of construction jobs.

U.S. Housing Starts

This contraction in construction jobs

was devastating when added to the already massive loss of

manufacturing jobs that occurred shortly after 2000.

U.S. Manufacturing Jobs

|

A

“post-securitization” credit crisis

The current crisis has the

distinction of being the first “post-securitization”

credit crisis, and so it has many unfamiliar features.

source

Unlike the LTCM crisis of 1998

or the stock market crash of 1987, which bore the hallmarks of

crises driven by a collapse of confidence, the current crisis

has its roots in the credit losses of leveraged financial

intermediaries. Liquidity injections by the central bank are

an invitation to the financial intermediaries to expand their

balance sheets by borrowing from the central bank for

on-lending to other parties. However, a leveraged institution

suffering a shortage of capital will be unwilling to take up

such an invitation. Recognition of this reluctance is the key

to understanding the protracted turmoil we have witnessed in

the interbank market.

Mortgages and asset-backed

securities built on mortgage assets are held in large

quantities by leveraged institutions — by the broker-dealers

themselves at the warehousing stage of the securitization

process, by hedge funds specializing in mortgage securities,

and by the off-balance-sheet vehicles that the banks had set

up specifically for the purpose of carrying the mortgage

securities and the collateralized debt obligations that have

been written on them.

SIVs (structured investment

vehicles) have played an important role in the current crisis.

Conduits and SIVs were designed to hold mortgage-related

assets funded by rolling over short-term liabilities such as

asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). However, during the

initial stages of the crisis (roughly mid-August 2007), they

began to experience difficulties in rolling over their ABCP

liabilities. Many of the off-balance-sheet vehicles had been

set up with back-up liquidity lines from commercial banks, and

such liquidity lines were beginning to be tapped by

mid-August.

As credit lines were tapped,

the balance sheet constraint at the banks must have begun to

bind, making them more reluctant to lend. In effect, the banks

were “lending against their will.” The fact that bank

balance sheets did not contract is indicative of this

involuntary expansion of credit. One of the consequences of

such an involuntary expansion was that banks sought other ways

to curtail lending. Their natural response was to cut off, or

curtail, lending that was discretionary. The seizing up of the

interbank credit market can be seen as the conjunction of the

desired contraction of balance sheets and the “involuntary”

lending due to the tapping of credit lines by distressed

entities.

Other factors, such as concerns

over counterparty risk and the hoarding of liquidity in

anticipation of new calls on the capital of the bank would

certainly have exacerbated such trends. However, the

hypothesis of an “involuntary” extension of credit appears

important in explaining some of the salient features of recent

credit market events.

source

Financial markets perform the

essential economic function of channeling funds to those who

have productive investment opportunities (which can include

consumer purchases of goods and houses). ...this function of

financial markets is critical to a well-functioning economy;

without it, countries, and their populations, cannot get rich.

Enabling financial markets to effectively perform this

essential function is by no means easy; financial markets must

solve information problems to ensure that funds actually go to

those with productive investments, so that they can pay back

those who have lent to them. Financial development involves

innovations or liberalization of financial markets that

improve the flow of information. Unfortunately, however,

financial liberalization and innovation, often have flaws and

do not solve information problems as well as markets may have

hoped they would. When these flaws become evident, financial

markets sometimes seize up, often with very negative

consequences for the economy.

...we have been experiencing

exactly such a cycle in recent years. Advances in information

and communications technology have allowed for faster and more

disaggregated mortgage underwriting decisions. A mortgage

broker with an Internet connection could quickly fill out an

online form and price a loan for a customer with the help of

credit-scoring technology. The same technological improvements

would allow the resulting loan to be cheaply bundled with

other mortgages to produce mortgage-backed securities, which

could then be sold off to investors. Advances in financial

engineering could take the securitization process even further

by aggregating slices of mortgage-backed securities into more

complicated structured products, such as collateralized debt

obligations (CDOs), to tailor the credit risks of various

types of assets to risk profiles desired by different kinds of

investors.

As has been true of many

financial innovations in the past, the benefits of this

disaggregated originate-to-distribute model may have been

obvious, but the problems less so. The originate-to-distribute

model, unfortunately, created some severe incentive problems,

which are referred to as principal-agent problems, or more

simply as agency problems, in which the agent (the originator

of the loans) did not have the incentives to act fully in the

interest of the principal (the ultimate holder of the loan).

Originators had every incentive to maintain origination

volume, because that would allow them to earn substantial

fees, but they had weak incentives to maintain loan quality.

When loans went bad, originators lost money, mainly because of

the warranties they provided on loans; however, those

warranties often expired as quickly as ninety days after

origination. Furthermore, unlike traditional players in

mortgage markets, originators often saw little value in their

charters, because they often had little capital tied up in

their firm. When hit with a wave of early payment defaults and

the associated warranty claims, they simply went out of

business. While the lending boom lasted, however, originators

earned large profits.

Many securitizers of

mortgage-backed securities and resecuritizers, such as CDO

managers, also, in retrospect, appear to have been motivated

more by issuance and arrangement fees and less by concern for

the longer-run performance of these securities.

source

Crisis

Compels Economists To Reach for New Paradigm

The

Leverage Cycle

source

|

|

|

Why all the

U.S. debt?

Watch this... Video

1, 2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9

see... Money

As Debt, II,

III,

IV

Federal Government Debt: Total Public Debt

source

U.S. Debt held by the public as a

percentage of GPD source

|

|

Follow the

Money...

What

in the world is going on?

Wealth is

leaving the U.S. |

|

1.)

Dollars flow from U.S.

to petroleum-exporting nations.

Public debt as a percent of GDP

(2011) map

source

Flows of Oil map

source | petroleum

exporter list

|

|

and

|

|

2.)

Dollars flow from U.S.

to merchandise-exporting nations.

Foreign currency reserves and gold

minus external debt (2010) map

source

Flow of Manufactured Goods (2004) map

source | merchandise

exporter list

|

|

and

What

is going on in the U.S.?

Wealth is

being transferred inside the U.S.

|

|

3.)

Dollars flow

into U.S. social

welfare programs,

which were initiated as part of the New Deal

resulting from

the progressive

movement (Hoover,

Roosevelt,

Johnson)

and the so-called second

Bill of Rights.

Social

Security Deficits

Social Security Primary

Surplus/Deficits (2005-2011)

source

Medicare

Deficits

Medicare

Surplus/Deficits

(Income minus

Expenditures)

($s in Billions)

Medicare

Surplus/Deficits (2005-2010)

source |

|

What about the GDP?

|

|